An interesting titbit from Peter Simkins’ book, Kitchener’s Army, which I mentioned in my last post. It’s the story of a young nurse, Grace Hume, whose horrific death and mutilation at the hands of the Germans in Belgium in September 1914 was reported in the Dumfries Standard. According to the report, the Germans attacked the field hospital where Grace was working, killing wounded men. A horrific war crime in itself, but it wasn’t the worst of it. The invading soldiers then ‘cut off Nurse Hume’s right breast, leaving her to die.’

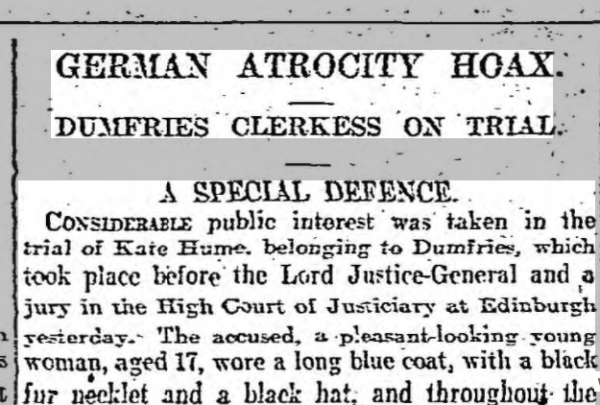

Naturally, the account, based on a letter produced by Grace’s 17-year-old sister, Kate, provoked a wave of outrage, hysteria and anti-German hatred.

The only problem was, it wasn’t true. The letter was fake. Kate had made the whole thing up.

Grace Hume was alive and well, living in Huddersfield. She was a nurse, but she had never set foot in Belgium.

The story of Grace Hume and her sister piqued my curiosity. I dug a little deeper, logging into the online British Newspaper Archive to try to find out a bit more.

The ‘Bogus Letters Case’ was reported in a number of newspapers. The account in the Scotsman, reporting Kate’s trial in Edinburgh on 29 December 1914, is particularly full and illuminating. It even quotes from the two letters that sparked the whole thing. The first purported to be from Grace, and is so preposterous that it’s unclear how anyone could have taken it seriously. It was supposedly found clutched in the dead nurse’s hand:

‘Dear Kate,

This is to say goodbye. Have not long to live. Hospital has been set on fire. Germans cruel. A man here has had his head cut off, and my right breast taken away. Give my love to – .

Goodbye,

Grac.’ [sic]

The second letter appeared to be from one J.M. Mullard, a nurse with the Royal Irish Troop. Nurse Mullard claimed that she had been with Grace when she died and had been charged with delivering Grace’s letter to her sister. She supplied further gruesome details of Grace’s murder: two Germans had cut off her right breast and were in the process of cutting off her left when they were killed by a British soldier. Nurse Mullard related how Grace had died ‘in great agony’. She also related details of Grace’s life in Belgium, which apparently involved riding a horse around the battle field, looking for wounded men:

‘On one occasion, when bringing in a wounded soldier, a German attacked her. She threw the soldier’s gun at him and shot him with her rifle. Of course all nurses here are armed…’

Again, how could anyone believe this nonsense? And how could the Dumfries Standard have published the letters? It’s clear the reporter and editor made no attempt to confirm the details. If they had spoken to Grace’s father, they would have discovered that he had received no telegram from the War Office informing him of Grace’s death. And also that she wasn’t even a fully certified nurse, and so was unlikely to have been sent to the front at this time. Neither did she know how to ride a horse or shoot a rifle. The journalists made no attempt to verify the facts at all.

But by then the story was already widespread in Dumfries. Word had got around. Kate had shown the letters to the family she lodged with. They had obviously repeated it and now the horrible fate of the heroic ‘murdered’ nurse was on everyone’s lips. The reporter who got the forged letters from Kate was feeding a monster that had already been created. Perhaps he and his editor never believed in the authenticity of the letters. But they knew it would make good copy and sell newspapers.

It’s easy now to say ‘how could anyone believe it?’, knowing as we do that it’s false. But the story fed into people’s beliefs at the time. This was the kind of atrocity they had been told the Germans perpetrated. It confirmed their prejudices. And doesn’t everyone love to have their prejudices confirmed?

When it comes down to it, they wanted it to be true. They needed it to be true.

But for me, the biggest question of all is, why did Kate do it?

The answer to that will have to wait for another post.

Read Part 2 here.