Spring. 1880.

It was General Krolikov’s name day, the day he celebrated being Timofei son of Timofei.

He chose to spend it in Tavrichesky Garden, St Petersburg, as he did every year, weather permitting. As usual, his daughter Vera had arranged a party. Most of those in the group were strangers to him. He assumed they were members of his family. Nephews and nieces who had grown up in his absence. Distant cousins and their interchangeable offspring. And now there was a whole gaggle of brats running around his legs. Someone had even brought along a yapping dog, one of those awful miniature lapdogs. He wouldn’t mind if it was a proper hound.

He only ever saw his relatives on his name day. And between one year and the next, he forgot all their names.

Why were they here? What did they want from him? They brought him gifts he didn’t want. What did they expect from him in return?

No doubt they thought he was rich, because of his connections at court and his years of colonial service. No one came back from the Caucasus poor, no one sensible did.

Well, maybe he was rich, but they weren’t getting their grubby hands on any of his fortune.

He hated the way they simpered and fawned. Was that why his name day always put him in a bad mood? They smiled like imbeciles. No, it was worse than that. They smiled as if he were the imbecile. And he knew what they wanted. They wanted him to remember them, to say their names without prompting.

Because then there was a chance that he would remember them in his will.

Krolikov smiled to himself. Fat chance of that!

There were picnic baskets and bottles of champagne. One of the advantages of growing old was that he didn’t have to lug anything. The nameless relatives vied with each other to carry the heaviest burden, making sure that he saw them. See, uncle! their faces beamed. More fool them. He didn’t ask them to. Why not leave it to the servants?

But when he looked around, he couldn’t see any servants.

‘Where is Grigory?’ he growled.

Vera was at his side. ‘Grigory? Don’t you remember, father? We talked about this?’

‘Talked about what?’

‘I gave all the servants the day off.’

‘All of them? Why on earth did you do that?’

‘Because we have no need of them. The boys can carry everything.’

‘You shouldn’t have done it without consulting me.’

‘But I did consult you, father. You agreed.’

‘No. I would never agree to it.’

‘Well, you did.’

Krolikov lapsed into a reflective silence. Perhaps he did remember something about it now.

‘Who are these people?’

‘They are all the people who love you, father.’

‘Jesus Christ.’

He noticed Vera watching him solicitously.

‘But where are my friends?’

‘We are your friends.’

’No, my real friends. Dmitri Petrovich, Alexei Andreevich, Boris Borisovich.’ Krolikov looked about him, growing suddenly agitated. ‘They are not here. And where are my brothers, Mikhail Timofeevich and Pavel Timofeevich?’

There was a beat before Vera replied: ‘They are all dead, father.’

He winced at the brutality of her statement, wanted to punish her for her cruelty with a reprimand. ‘Why didn’t you invite the Emperor?’ he demanded sharply.

‘I did, father. He sent his apologies.’ Vera looked away from her father and muttered under breath: ‘As he does every year.’

‘What about the Empress?’

‘The Empress is very ill. They say she is dying.’

He came to a sudden stop on the path that led between an avenue of English oak trees. The whole park was laid out in the English style.

The party carried on without him. So that was how much they cared about him. They didn’t even notice when he wasn’t there among them. Even Vera had walked on a few paces. But at least she stopped as soon as she noticed he was no longer by her side.

She looked back at him with an expression of mute appeal.

He waved her on with a bad-tempered flick of his cane. ‘I just want a moment to myself. Is that too much to ask? On my name day?’

Vera’s look was now one of hurt, which quickly changed to disappointment. She turned her back on her father and hurried to catch up with her husband and her own daughter, who were in amongst the other relatives.

The day was fine but chilly. Although winter was behind them, the party had come out in overcoats and scarves. Krolikov felt the ice still there deep in his bones. The sun glinted unreliably through the gently swaying leaves, coming and going like an elusive memory.

There was a rustle of branches, and the place felt suddenly alien to him. Perhaps it was the unfamiliar foreign plants coming into bloom, or the subtle eccentricities of the landscape. But as he stood there an odd feeling came over him. He wondered where he was and how he had got there.

At that moment, from somewhere to his left, a peal of laughter reached him. It was light, musical, a young girl’s laughter. A child mocking him? One of his confounded great nieces perhaps.

He turned in the direction of the sound and saw a girl of around eight or nine standing between two trees. She was dressed as a Circassian bride. Her silken bodice and skirt glinted a deep crimson, braided with gold. The domed headwear made her look like a strange and poisonous mushroom.

The girl stared directly at him, her eyes twinkling with impish mischief. She held her arms out to the sides, trailing a pair of long, loose sleeves like fairy wings.

As soon as he looked at her, she spun round, so that the veil that hung from the back of her headdress fanned out like a net cast into the air. Then, skipping away deeper into the wooded area, she was gone. But even in the second that he had seen her, he knew.

He knew that it was her.

It was a little strange, he had to admit, that she was still a child. It was so many years ago now since he had last seen her. And yet, at the same time, it felt like it was only yesterday. But he was certain that it was her, the little minx. He would recognise those eyes anywhere.

More and more these days, Krolikov felt himself living in the past and the present simultaneously. As for the future, it interested him less and less, although others still tried to draw him into it.

At first it had frightened him, this slippage in time. But he had now reached a point where he welcomed it. Often, he experienced this living past as a pleasant dream. Or at least, that was how it always started. The years fell from him and he was young again.

There had been times, however, when the dream turned out to be not so pleasant. It would start innocuously enough, teasing him in with some tantalising vision of an old, long dead comrade. But then it would quietly and without warning unleash a vision of horror, or shame, or perhaps a combination of both, because the worst horrors were those for which he was to blame.

And so always there was a sense of foreboding as he felt the dream approach. Where would it take him this time?

Krolikov heard her tinkling laughter recede behind a screen of trees and stepped off the path to follow it.

He quickened his step into a headlong lurch, using his cane to keep his balance on the rougher ground. Massive roots snared his staggering feet. Hanging branches scratched his face. The lower, thicker boughs blocked him, so that he had to duck beneath them, or find another way through.

From time to time, he lost the trail. He would stand and listen, then catch sight of a flash of crimson and head off after it.

She led him into a small clearing, enclosed by a ring of trees whose sprawling branches meshed together overhead to form a dense canopy. It was a dark place, sunless and chill. What light there was, came refracted through leaves. It flickered in the air and fell lifeless on the dappled ground.

In the centre of the clearing, with its back to Krolikov, there stood – Krolikov couldn’t say with certainty what it was, but it seemed to be a figure formed from shadows condensed into human form.

He – for the figure seemed to be male – was wearing a long black coat which went almost to the ground, and a top hat decorated with black crape as if in mourning. The man, or possibly youth, was shorter than Krolikov. The general was in his seventies but despite his age, still presented a fine, tall figure, always standing straight and high with a proud, military bearing.

On the ground to one side of the mysterious youth lay a carpet bag. Krolikov immediately conceived an irrational dread of what the bag contained.

The girl had taken up a position on the other side, facing Krolikov. She giggled, a little nervously, he thought, before dancing off towards the edge of the clearing.

The figure began to turn slowly towards him.

This was the moment in the dream when the horror would be revealed.

And so it was. A pleasant, youthful face now confronted him, handsome, almost feminine. But the pleasing impression of the face was spoilt by its expression of wry mockery.

And the youth was holding a sword out in front of him.

Eyes locked on Krolikov’s, the sinister figure began to spin the sword. The air sang as it was whipped by steel. The blade fractured into multiple ghostly images of itself. The youth’s hand hardly moved, but the sword swirled in ceaseless motion.

The last time he had seen such swordsmanship was in the Caucasus. His men captured one of the mountain dwellers, who put on a defiant display for them.

Krolikov was rooted to the spot, mesmerised. Where would the dream end this time?

The youth took three brisk steps towards him. The sword’s rapid swirling did not falter. The air sucked in its breath one final time.

Krolikov watched the blade’s relentless swoop. By the time he realised it was aimed at him, it was too late.

There was another glassy tinkle of laughter. Then nothing.

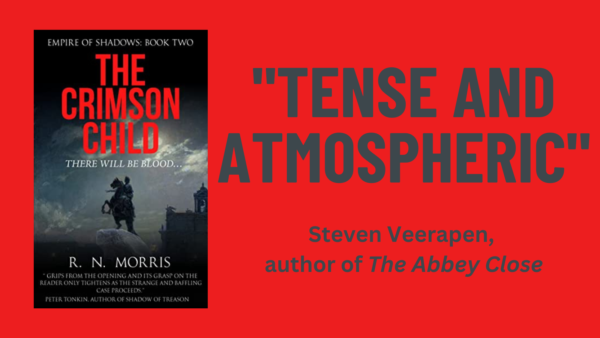

To read on, download The Crimson Child ebook for free on Kindle Unlimited, or buy for £3.99.